The Bhagavad Gita, Chapter XVIII: Reflections within the final chapter with

Kashmir Shaivite Swami Lakshmanjoo and other saints, sages, savants & scholars

An Introduction:

It has been a few years now since I wrote my comments on the Bhagavad Gita. I

consider the Bhagavad Gita as the one best source of wisdom-knowledge available.

It is the distillation, the essence of all the other Sanskrit texts brilliantly

conceived, interwoven and connected by Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa. The Gita is

within the Mahabharata, chapters 25 to 42 of the Bhishma Parvan (the Book of

Bhishma). The Kashmir Shaivite Abhinavagupta has said that the Bhagavad Gita has

the power to enlighten. I agree whole-heartedly. In these new writings I will

focus on the last final summing up Chapter XVIII, which I previously

intentionally left for a later day. Through the lenses of great scholars, sages

and saints - in whose steps I have gratefully followed - I hope to weave various

layers of reflections on this superbly liberating poem, along with my own born

in humility from Grace and Love.

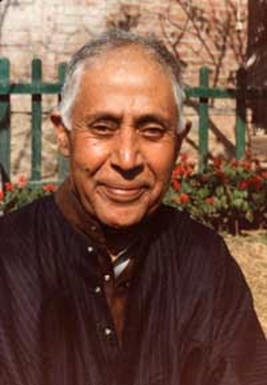

Swami Lakshmanjoo (1907-1991)

“The Bhagavad Gita in the Light of Kashmir Shaivism” as revealed by Kashmir

Shaivite saint and scholar, Swami Lakshmanjoo was in part initially recorded in

Nepal by John & Denise Hughes in 1990. This Kashmiri version of the Bhagavad

Gita, the complete eighteen chapters with commentaries, was published in 2013 by

The Universal Shaiva Fellowship, and is available as a hardback book that

includes a set of 27 DVDs – and a more affordable paperback version to be

released soon. Its publication is the child of the many years of love,

sacrifice, self-less dedicated service required to record and collect Swami

Lakshmanjoo’s teachings, and a rigorous concentrated effort to maintain a high

degree of perfect and correct Sanskrit scholarship.

John & Denise Hughes have generously granted me permission to quote from Swami

Lakshmanjoo’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita, which is based on the commentary

of the Kashmir Shaivite genius and enlightened sage Abhinavagupta (975-1025 AD).

In 1933 at the age of twenty-six Swami Lakshmanjoo published the unique Kashmiri

Sanskrit recension of the Bhagavad Gita, used by Abhinavagupta for his

commentary, which differs from other available recensions. There are fifteen

additional verses in the Kashmiri recension. The recent publication of Swami

Lakshmanjoo’s revealed translation is an event many of us have been eagerly

waiting for. Swami Lakshmanjoo possessed perfect memory and was “extremely

well-read, well-informed in Eastern and Western religious and philosophical

traditions” [John Hughes].

Truthfully I do feel that Kashmir Shaivism for me is the ultimate teaching, the

highest understanding and source of Truth, Wisdom-Knowledge, and traditional

primordial metaphysics. However I have also found value in exploring other

commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita. Thus I will wander in the delight of

reflecting insights from the polymath K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya, Swami Muni

Narayana Prasad, J.A.B. van Buitenen, Boris Marjanovic, Winthrop Sargeant, and

others.

I was not fortunate enough to have studied with Swami Lakshmanjoo, nor did I

ever meet him. I had completed my own commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita in 2006

when I began a serious concentrated study of the Shiva Sutras as translated by

Jaideva Singh and as I read the various other Kashmir Shaivite texts translated

by Jaideva Singh, like so many before me, I began to notice Jaideva Singh’s

repeated declarations of gratitude to Swami Lakshmanjoo. One feels that Jaideva

Singh admits that without Swami Lakshmanjoo to guide him through the encoded

Sanskrit in the Kashmir Shaivite texts, Singh would have been lost. I began to

order Swami Lakshmanjoo’s work, literally everything published by John & Denise

Hughes at the Universal Shaivite Foundation in Los Angeles.

In 2008 I unexpectedly moved to New Zealand and here began to intensely listen

to and watch the DVDs recorded by John Hughes. I immersed myself in the lectures

and affectionately began calling Swami Lakshmanjoo simply Lakshman, which

according to John & Denise is what he called himself. I cannot say when or even

exactly what happened during this ‘immersion’ period, but I know that my

consciousness shifted, was irreversibly altered as I experienced and was touched

by his ‘Grace’ in ways that changed me forever. I cannot sufficiently express my

gratitude to Swami Lakshmanjoo — and to John & Denise Hughes for all the hours

they spent on cold Kashmir floors recording Lakshman’s words. They hold the

treasure storehouse of what may be the last Wisdom-Knowledge remaining in this

Kali Yuga.

Kashmir Shaivism is not easy. There are many Sanskrit terms that at first seem

impossibly arduous, but the task is light compared to being trapped in this

miasma of amnesia and ever-expanding webs of delusion through endless cycles of

time. Swami Lakshmanjoo is the proverbial jewel beyond price, the boat that

carries us across this sea of ignorance and delusion. Over the years I have many

times made plans to travel to India and Kashmir, but destiny always had other

ideas. Perhaps my sweet longing was fulfilled by John & Denise Hughes, who

brought Swami Lakshmanjoo to me. Thank you.

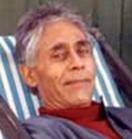

K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya (1918-1994)

K.K. Nair took the pen name Krishna Chaitanya. Whenever I read his books, which

I have gone to great trouble to even locate and expense to purchase, I am struck

by the madly incomprehensible thought that his brilliant insightful works are

out of print! I am completely bewildered by this and often find myself feeling

emotional, sad and even a bit angry that India could have forgotten this

wonderful man, both polymath and poet whose keen sensitive mind was wide and

capable of embracing all knowledge east and west, who during his life was

awarded every possible honour and published forty beautifully written books.

In a collection of his papers, Suguna Ramachandra has written a profile of K.K.

Nair/Krishna Chaitanya and said: “The record of work of Krishna Chaitanya…is in

many respects unique…his major projects have been hailed with a shower of

superlatives by scores of critics; they have been called stupendous, monumental,

phenomenal, colossal, their vast groundwork baffling comprehension.”

The accomplishments of K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya have been compared to Thomas

Aquinas, Teilard de Chardin, Dante, and even Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa, the

author of the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad Gita. Apparently, according to Suguna

Ramachandra, this last comparison to Vyasa upset K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya

“for [as he was] capable of deep reverence where it is due, he regards it a

sacrilege to bracket him with the thinker whom he hero-worships.”

Suguna Ramachandra: “He [K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya] has worked incessantly all

his life for a recovery of certitude, of the faith in the benignity of existence

and man’s possibility of realising meaning in life, which have been shattered by

the accumulation of segmental knowledge, more and more about less and less,

without an integrative wisdom.” And this was years before the twittered mush

vagaries of the Internet!

A review of his 'Gita and Modern Man' in the Hindustani Times, July 5, 1987:

“The magnum opus of his brooding brilliant mind, this book of Krishna Chaitanya,

the fabulous polymath, is the work of a life-time. As he sees it, Vyasa was

attempting an integration of knowledge, from the physics of matter to the psyche

of man. …No recent writer comes anywhere near him.”

In his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya argues for

enlightened acts that contribute to the well being of the world, acts that are

grounded in the knowledge that we are all the One, acts that are not selfishly

motivated. I feel that his ‘The Gita for Modern Man’ is both a profound

excellent understanding of Vyasa’s vast intended Wisdom and a practical guide to

those who have dedicated themselves to making a difference, who are working as

he says for the ‘weal’ of the world. He also wrote a wonderful book on the

Mahabharata, which focuses on the deeply fascinating complexity and symbolism in

the individual characters. I will expand on K.K. Nair/Krishna Chaitanya’s life

and ideas in a separate article.

Swami Muni Narayana Prasad (1938 -)

Although I know little about Swami Muni Narayana Prasad, I began reading him

because he had translated many of the Upanishads. I was struck by his refreshing

ability to directly communicate the meaning of the texts in powerful yet simple

language. It seemed obvious to me that his understanding was so great, profound

and comprehensive that he was able to write the essence of these ancient texts

as concisely as humanly possible and in an accessible down-to-earth modern

English. His translation of the Mundaka Upanishad really influenced my thinking

and I began to buy his other publications, including the Bhagavad Gita.

Swami Muni Narayana Prasad was born in 1938 in Kerala, India. He graduated from

Engineering College Thiruvananthapuram (the capital). From 1960 he lived in

Narayana Gurukulam as a disciple of Nataraja Guru. He has authored over 90 books

including commentaries on the Katha, Kena, Mundaka, Prasna, Taittiriya, Aitareya

and Chandogya Upanishads. The official language of Kerala is Malayalam. He is

obviously a wonderfully gifted writer and I am grateful that he decided to

devote part of his life to the difficult task of translating these sacred

Sanskrit texts into the more limited and certainly less expressive English

language.

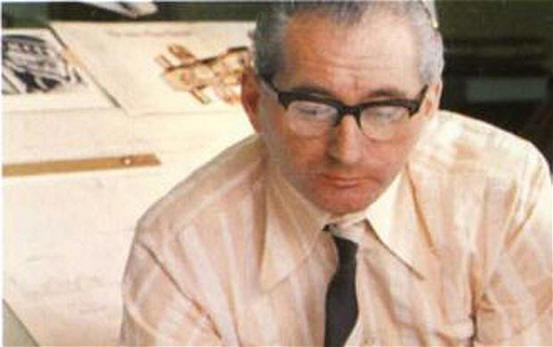

J.A.B. van Buitenen (1928-1979)

J.A.B. van Buitenen is the Sanskrit scholar whose brilliant incomplete

translation of the Mahabharata first seduced me, back in the late 1980s, into

the endlessly fascinating epic world of the Bharatas. His translation of the

Bhagavad Gita remains one of my favourites and I often consult him when I am

perplexed. When a particularly subtle meaning eludes me, I ask myself, “What did

J.A.B. van Buitenen say?” and head for his straightforward clean translation,

which praise the heavens, is still in print. Thank you.

Boris Marjanovic

Boris Marjanovic ‘discovered’ the Kashmir Shaivite saint and genius

Abhinavagupta as a graduate student at the University of Iowa and “felt an urge

to absorb and internalize his teachings.” In 2002 Indica Books in Varanasi,

India published Marjanovic’s translation of Abhinavagupta’s commentary on the

Bhagavad Gita. As Marjanovic says in his introduction, “…reading [Abhinavagupta’s]

original texts requires much more than a knowledge of Sanskrit. …their

comprehension is not only dependent on the intellectual understanding of the

philosophical system, but also on the experience which comes as a result of

practice.”

In my own pursuit to understand the Bhagavad Gita, I found Marjanovic’s

translation enormously helpful. It was an expansion of the other translations

and I agree as he points out, only those who are actually practicing meditation

and proceeding experientially into higher states of consciousness will truly

appreciate Abhinavagupta’s teachings. Marjanovic quotes from Swami Lakshmanjoo’s

‘Kashmir Shaivism: The Secret Supreme’ in his introduction. Once again we see

evidence that all the scholars who were interested in Kashmir Shaivism sought

out Swami Lakshmanjoo.

Marjanovic explains the basics of Kashmir Shaivism in the introduction and one

of the most intriguing aspects of this school is that Abhinavagupta advises

those who have not yet attained perfection and are engaged in practice “not to

withdraw form the world but to enjoy the objects of the senses while at the same

time continuing the practice of deep meditation.” The Oneness is ubiquitous

all-pervading everywhere and everything, so what is not sacred? It is only our

deluded state of ignorance that makes us feel we must reject the world.

Abstaining from life never works — and in fact remaining in God-Consciousness

while engaging in worldly activities is far more difficult. “As a result of this

experience a yogin perceives all beings as part of the Divine." [BhG V.19]

I’m certain a few more of my favourite sages will join this adventure, and I

could not easily find my way through the Gita’s Sanskrit without Winthrop

Sargeant (1903-1986), who also was an aspiring violinist and professional music

critic. Sargeant’s Bhagavad Gita is essentially a dictionary; in his words, “an

interlinear word-for-word arrangement…the metrical formation of the poem’s

stanzas, and their grammatical structures.” I don’t always agree with Sargeant’s

beautiful translations, but his book is invaluable and my copy is filled with my

colour-pen notes and happily falling apart from love.

So I invite you to join me on another journey into my beloved Bhagavad Gita, the

final Chapter XVIII, always remembering as Swami Lakshmanjoo has so wisely said,

“However much you tried to do it, but it was, in the long run, it was for

realizing the truth of God, so it was Divine.”

We meet in the Heart,

V. Susan Ferguson

"This whole universe has come into existence just to carry you to God

consciousness." - Swami Lakshmanjoo, The Shiva Sutras

Bhagavad Gita, In the Light of Kashmir Shaivism, with original video, Revealed

by Swami Lakshmanjoo, Edited by John Hughes, Co-editors Viresh Hughes and Denise

Hughes; Universal Shaiva Fellowship, 2013.

The Gita for Modern Man, by Krishna Chaitanya; Clarion Books, Associated with

Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi, 1986, 1992.

KRISHNA CHAITANYA, A Profile and Selected Papers; Edited by Suguna Ramachandra;

Konark Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Delhi, 1991.

Life’s Pilgrimage Through The Gita, by Swami Muni Narayana Prasad; D.K.

Printworld, New Delhi, 2005, 2008.

The Bhagavad Gita in the Mahabharata, A Bilingual Edition, translated by J.A.B.

van Buitenen; The University of Chicago Press, 1981.

The Bhagavad Gita, translated by Winthrop Sargeant; State University of New York

Press, 1994.

|

Questions

or comments about articles on this site: Email V. Susan Ferguson: Click Here |

Copyright© V. Susan Ferguson All rights reserved. |

Technical questions or

comments about the site: Email the Webmaster: Click Here |